By Abigail Reid & Samantha Villaire & Eleni Andris*

The Argus, a creature from Greek mythology, has one hundred eyes that never close at the same time. It represents a “never-sleeping crusade”, a fitting namesake for the first African-American newspaper in St. Louis, determined to fight for the rights of the black community at a time when political privileges and social equality were limited[1].

Originally established in 1912 at 2314 Market St. by brothers Joseph and William Mitchell, the paper has a long and inspiring history. Determined to get the paper off the ground, Joseph and William brought their relatives over from Alabama to train as linotypists, engravers, and printing operators. They had limited start-up funds to pour into the venture, but were determined to provide organization, structure, and voice to the black community. With no operating or printing machines at the onset, the brothers paid a friend $35/week to print the newspaper until they were eventually able to establish their own printing press before too long. Having access to their own printing press allowed the paper to grow and reach more people.

The paper’s early years were unpredictable and unstable. As Dr. Symington Curtis, son of Dr. Thomas Curtis, an early partner in the project, described the period: “during its early years (1911-1925) the Argus did not succeed financially… Mr. J.E. Mitchell, however, through much adversity continued to publish…”. Mitchell’s resolve paid off, however, as the Argus became one of about 200 black newspapers out of around 3,000 nationwide, established since 1827, to survive through financial troubles.

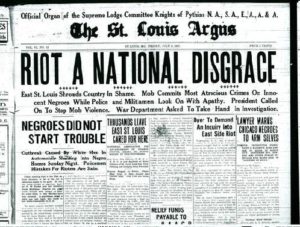

J.E. Mitchell took advantage of the platform he had worked so hard to build and preserve, using it to address everything from discriminatory business practices to Ku Klux Klan violence. His voice became a prominent battle cry: “We hold that…if Uncle Sam does nothing for the protection of the colored people in cases where it is the government’s plain duty, that in itself gives encouragement to all kinds of other evils as injustices in the courts and other petty discriminations,”[3] he wrote. Mitchell also had visions of better schools/educational opportunities, and full Civil Rights, of which he took to the Argus to write about in the hopes that his words would reach civilian and political ears[4].

The St. Louis Argus played an influential role in helping to organize and advertise boycotts and protests during the Civil Rights Era. The Jefferson Bank Demonstrations, a set of boycotts and sit-in’s at the bank, for example, occurred because the bank did not employ African Americans. Any African American who was working there was part of the janitorial staff. The Argus covered and participated in the demonstrations, helping to expand the local vernacular surrounding the plight for the racial equality[6].

The St. Louis Argus also helped sponsor programs that political movements that supported black St. Louisans through a variety of civic platforms. The Citizen’s Liberty League, for example, noted as one of the first and most important political Negros movements in St. Louis, was sponsored by the Argus[8]. Together the Citizen’s Liberty League and Argus helped African Americans gain jobs in the fire and police departments, increasing black power in politics as well[9].

Today the St. Louis Argus looks different. In 2007, a man named Eddie Hasan purchased the paper from Eugene Mitchell , the grandson of the Argus’ original two founders, and hired Antonio French (well known Democratic political activist) and George Jackson (pseudonym for a black journalist who needs to remain anonymous to keep his other job) to breathe new life back into the publication and increase its viewing. Their plan consisted primarily of improving and increasing technological use, including launching a website and updating printing machinery. Together the two helped uplift the St. Louis Argus into the modern era[10].

The St. Louis American was founded in response to the Argus in 1928. Judge Nathan B. Young and several other recognized African American businessmen, including Homer G. Phillips, felt that there was a need for a paper that provided an alternative perspective to the singular conservative African-American newspaper available to the black community at the time. The paper was housed out of the Peoples Finance Building, a structure erected in 1925 and founded by the Peoples Finance Corporation, the largest African-American finance company in the world[11]. The building was not only home to The St. Louis American but also to some of St. Louis’ other finest African American businesses as well, including doctors, lawyers and photographers, as well as the J. Roy Terry School of Music, the Moving Picture Operators Union, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (N.A.A.C.P.), the Peoples Finance Corporation and the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters[12]. Consequently, it was known as a business “hub”, and attracted a lot of prominent members of the black community to its space.

Nathan B. Young firmly believed in the boundless depth and wealth of history that the city of St. Louis touted, and held that “if you wanted the story of the history of civil rights in the U.S.A. and had to confine it to one city, you could write the entire story of civil rights by going back to the history of the city of St. Louis.” The St. Louis American was a platform “like no other” for him to be the “voice of authority as far as civil rights”. He was known by historians for being “one of these pioneering historians of the black experience in St. Louis”, so integrally intertwined in the civil rights movement that “it’s pretty hard to talk about civil rights in St. Louis without crediting Judge Young and his great work” (Gwen Moore, Missouri Historical Society Curator)[13].

The paper went on to enjoy great success, providing The American readers with information relevant to their lives. Young started at the newspaper as a lawyer, but ended up working as the editor/publisher for more than 43 years. His liberal insights, plastered across The American’s pages, tugged at moral and political strings. The paper’s first issue featured A. Phillip Randolph, leader in the Civil Rights Movement and the American Labor Movement[14] as an unsung hero. The article covered the Pullman Porters’, the first all-black union founded by Randolph, and their plight to try to get recognition. Young also piggybacked Yale classmate’s, founder of the Chicago Whip Joe Bibb, “Buy Where You Can Work” Campaign and brought it to St. Louis through the newspaper[15].

Young recruited Nathaniel Sweets who ended up publishing and owning The American for 45 years. Sweets joined The American as advertising manager in 1928, the year it was founded, and became publisher in 1933 and owned it until 1981. The American continued to gain respect throughout the years, and even welcomed visitors such as Malcom X to in 1955. In 1981 the paper was sold to its current owner, Donald Suggs[16].

The St. Louis American is still widely in circulation today, and has all of the fittings of a modern newspaper. Circulation and distribution is higher than ever, earning The American title as “the largest weekly newspaper in the state of Missouri” and the “the largest independent newspaper (daily or weekly) in Missouri, printing 70,000 copies each week”, all while retaining a robust multi-media platform, as the stlamerican.com is one of the “most-hit media websites in St. Louis”. The paper has also expanded into the world of social media to keep up with the next generation of perpetual information-seekers, updating their Facebook and Twitter regularly[17]. Through these varied approaches to news dissemination, The St. Louis American has found a way to stay relevant while other comparable newspaper outlets have disappeared overtime.

*Eleni Andris assisted in the compilation and synthesis of supplemental research

Sources:

[1] http://www.stlmediahistory.org/index.php/Print/PrintPublicationHistory/st.-louis-argus

[2] http://forums.smitegame.com/showthread.php?97361-Argus-The-All-Seeing

[3] http://www.stlmediahistory.org/index.php/Print/PrintPublicationHistory/st.-louis-argus

[4] http://www.stltoday.com/news/local/obituaries/dr-eugene-mitchell-dies-broke-glass-ceiling-for-blacks-here/article_3b521a4f-3263-5da7-8548-56dda94251e1.html

[5] http://historyhappenshere.org/archives/7916

[6] http://www.stlmediahistory.org/index.php/Print/PrintPublicationHistory/st.-louis-argus

[7] http://www.stltoday.com/news/archives/aug-protests-at-jefferson-bank-lead-to-major-changes-in/article_d6be4178-cc1f-527a-a0d0-fd78a720456e.html

[8] http://www.stlmediahistory.org/index.php/Print/PrintPublicationHistory/st.-louis-argus

[9] https://www.stlouis-mo.gov/government/departments/planning/cultural-resources/preservation-plan/Part-I-African-American-Experience.cfm

[10] http://www.stlmediahistory.org/index.php/Print/PrintPublicationHistory/st.-louis-argus

[11] ibid

[12] http://www.umsl.edu/virtualstl/phase2/1950/buildings/peoplesfinance.html

[13] http://www.stlmediahistory.org/index.php/Print/PrintPublicationHistory/st.-louis-argus

[14] http://ww.history.com/topics/black-history/a-philip-randolph

[15] http://www.stlmediahistory.org/index.php/Print/PrintPublicationHistory/st.-louis-argus

[16] ibid

[17] http://www.stlamerican.com/site/about_us.html