By Ryan DeLoach, Jenn DeRose

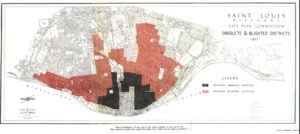

1947 City Plan

In 1907, the St. Louis Civic League published “A City Plan for St. Louis,” which made St. Louis the first city in the United States to develop a comprehensive city plan.[1] This plan presented a strategic vision for the future development and improvement of St. Louis. A few years later, many of the proposals outlined in the 1907 plan were taken up by the City Plan Commission, which was established by city ordinance in 1911.

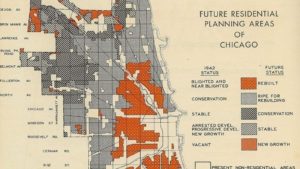

The St. Louis City Plan Commission became a dominant force in St. Louis city planning throughout 1920s and 30s under the leadership of Harland Bartholomew and came to influence city planning across the nation. As early as 1936, the City Planning Commission began to identify the first signs of central city abandonment in St. Louis, warning, “if adequate measures are not taken, the city is faced with gradual economic and social collapse. The older central areas of the city are being abandoned, and this insidious trend will continue until the entire city is engulfed.”[2]

In 1947, the City Planning Commission created the 1947 Comprehensive City Plan, which called for the clearance of large swaths of land in the heart of the city. Neighborhoods categorized as “blighted” were deemed in need of immediate repair, while “obsolete” neighborhoods were recommended for clearance and wholesale reconstruction.[3]

Federal Funding For Urban Renewal

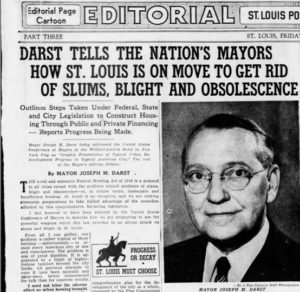

After the U.S. Congress passed the National Housing Act in 1949, power and resources were pumped into cities across the country for the clearance and assembling of land, making it possible for the city of St. Louis to enact the recommendations of the 1947 Comprehensive City Plan. In an editorial article published in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch on May 12, 1950, St. Louis Mayor Joseph Darst outlined how St. Louis planned to take advantage of the new law:

“The novel and extensive Federal Housing Act of 1949 is a godsend to all cities cursed with the stubborn related problems of slums, blight and obsolescence—or in simple terms, inadequate and insufficient housing. St. Louis is no exception, and we are making strenuous preparations to take fullest advantage of the remedies afforded by this comprehensive, far-seeing legislation…”

“The excessive cost of ground in the slum and blighted areas has always been a major stumbling block in previous attempts at redevelopment…Thanks to Title I, a way has finally been evolved to bring down costs of the ground, place it once more in the competitive market and make it attractive in the eyes of investors. The St. Louis program is gathering momentum, and the next few years should witness a vast transformation of whole neighborhoods that will change the very face of the city.”

Plaza Square Urban Renewal Project

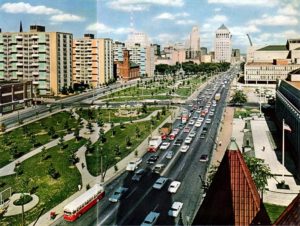

Preliminary plans of Plaza Square and a picture shortly after completion of the project in 1961.

St. Louis’s first project benefiting from this law was the Plaza Urban Renewal Area. Since 1907, city leaders had been developing plans for redevelopment of the area, and many local politicians described the area near city hall as an eyesore. A year after the creation of the Plaza Urban Renewal Area in 1950, the area became a Federally-assisted Title I Urban Renewal Project.[4] That same year, the state of Missouri created the Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority in order to capitalize on the funds being doled out by the federal government for slum clearance.[5]

After initial difficulties gaining voter support for the city’s share of the financing, a $1.5 million bond issue passed in 1953 to help get the project off the ground.[6] As the project launched, city leaders praised the marriage of public and private investment and began to envision ways in which this new partnership could be used to help rebuild the city.[7]

Mill Creek Valley Urban Renewal Project

The Plaza Square Project paved the way for St. Louis’s largest urban renewal project, Mill Creek Valley. Like Plaza Square, city planners had long dreamed of clearing and recreating Mill Creek Valley. Following on the heels of the 1947 Comprehensive City Plan, the Land Clearance Redevelopment Authority produced a report charting the substandard housing conditions in Mill Creek Valley. According to the report, 99% of the structures in the area were in need of major repairs, 80% were without private baths and toilets, and 67% did not even have running water.[8] On August 7, 1954, Mayor Raymond Tucker announced plans to demolish commercial and residential buildings across 454 acres in Mill Creek Valley. Following his announcement, front-page headlines praised Tucker’s bold vision to make St. Louis home to the nation’s largest urban-renewal project.[9]

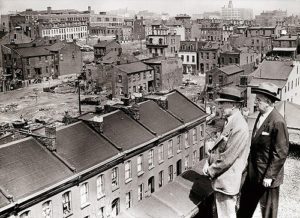

Mayor Raymond Tucker (on right) standing on a rooftop overlooking Mill Creek Valley in 1956.

When local residents heard the news that their neighborhood had been chosen for demolition, many protested, claiming that their neighborhood was not nearly as dilapidated as many others in the city. The Citizens’ Council on Housing and Community Planning defended the choice of the site by arguing, “No more dramatic example may be found than these 54 blocks located in the very center of our city…People going and coming from work through this district are offended by the state of decay they witness on all sides. Unfortunately, too, every visitor who arrives in our city by train is given a poor impression of St. Louis as he or she is transported immediately through such dismal districts.”[10]

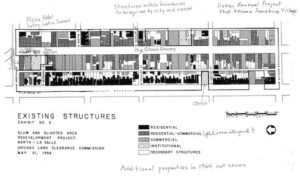

Piggybacking off of the success of the 1953 bond issue, city voters approved a bond issue of $110 in 1955, which set aside $10 million for urban renewal. Although the bond issue passed in 1955, considerable planning had to be done before land acquisition could take place in Mill Creek Valley. In 1958, St. Louis’s Land Clearance for Redevelopment Authority published the “Redevelopment Plan for Mill Creek Valley Project,” which called for the demolition of 93% of the neighborhood. In 1959, demolition of the neighborhood began, displacing over 20,000 residents, 95% of whom were black.[11]

Mill Creek Valley after demolition.

Financing the Project

The Mill Creek Valley clearance project was paid for by a variety of sources, within the public and private sector. The main source of funding came from the Federal Government, which allocated finances for slum clearance through Title I of the Housing Act of 1949.

The Board of Aldermen voted 27 to 1 to clear the neighborhood on Friday, March 28th of 1958, according the St. Louis Post Dispatch. The only dissenting vote was from Alderman Archie Blaine, who had 97% of the proposed clearance site in his ward, which was then in the 9th Ward. He voted no because there was “no provision for low income residents” for re-location. He told the St. Louis Post Dispatch that he was “in favor of better housing, but not in favor of moving slums to other parts of the city.”

According to a 2009 article in the St. Louis Post Dispatch reminiscing on the project, Saint Louis City voters “overwhelmingly approved a $10 million bond issue for demolition, on the promise that the federal government would reimburse most of it.”

The true net cost of clearing Mill Creek Valley, according to The Other Missouri History: Populists, Prostitutes, and Regular Folk, totaled $34,400,000.[12] The City of St. Louis paid $11,400,000, and the Federal Government paid $23,000,000. Private investments in the project totaled $250,000,000.

These numbers conflict with those identified in “History of Renewal,” a technical report written in 1971 on development programs in St. Louis, which was paid for by a grant under the Housing Act of 1949.[13] This document states that the City of St. Louis would contribute $7,037,058, the Federal Government would contribute $21,111,174, and private investors would contribute $125,936,232.

In reality, the City of St. Louis payed $11,400,000 to remove one of the most densely populated areas of the city and replace it with mostly nothing.

Interestingly, the St. Louis Post Dispatch, a strong supporter of the plan, had investments in the renewal fund for a land-clearance effort tied to Mill Creek Valley. According to “The History of Renewal” document, the “Urban Redevelopment Corporation of St. Louis was formed to redevelop the the Plaza Project. This corporation, a cooperative effort of local concerns was initiated by the St. Louis Post-Dispatch which pledged $250,000 to start a renewal fund. Seventy firms subscribed $2 million to provide the equity for the project.”[14]

Identifying other private sources will require further research to identify individual funders.

Newspaper Editorials and Public Perception

The strong public support for the clearance plan from all sectors made finding dissenting editorials difficult. In fact, Ernest Calloway, president of the St, Louis Chapter of the NAACP, said in a speech that the clearance project would “ revive the heart” of St. Louis and “slow down the stampede to the suburbs.”[15] The authors of this paper are certain that dissenting views must exist, but were not able to locate these editorials within the date ranges close to the many editorials and positive-leaning articles on the project published in the St. Louis Post Dispatch, whose enthusiasm for the project was made crystal clear in its “Progress or Decay” series on the subject of Mill Creek Valley.[16]

The St. Louis Post Dispatch, in a 1957 article on the proposed replacement for the “slum clearance project,” discusses the project’s proposed replacement – housing for 2,100 people planned with “calculated casualness” to replace the “slum.”

The choice of the word “slum” for the area and the flattering illustrations of the proposed street art and excited descriptions of the proposed superblocks also help to reveal the St. Louis Post Dispatch’s slant in favor of the clearance. Nearly every mention of Mill Creek Valley’s clearance, in both articles and editorials, mentions the decay of the buildings and abysmal conditions residents were living in, without discussing the vibrant community that existed within the neighborhood’s boundaries.

In a 1958 editorial, the St. Louis Post Dispatch published an article hailing the project as a progressive way to redirect the population and industry back towards the Mississippi River. The article suggests that the clearance plan should be emulated in other cities with troubled neighborhoods. The editorial was written by Joseph R. Passonneau, dean of the School of Architecture at Washington University at the time of his opinion piece. The editorial also boasts that the slums, which he claims were ruined beyond repair, would be replaced by the “finest neighborhood” in St. Louis, housing 2100 residents.

A few years later, in 1970, years after the abandoned site was nicknamed “Hiroshima Flats,” the St. Louis Post Dispatch published an article calling the project a success.

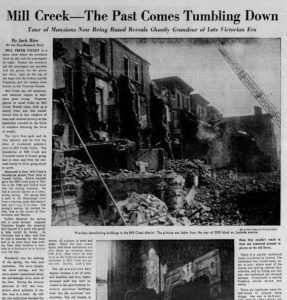

One editorial among many stood out for its melancholy take on the clearance. The article, written in October of 1959 by St. Louis Post Dispatch staffer Jack Rice, talks of the Victorian era mansions that looters stripped under the cover of darkness in the abandoned neighborhoods. The article speaks of the houses and their history with remorse for lost mansions and neighborhood status, but does not lament the fate of the residents displaced by the clearance project.

The editorial by Rice likened the draining of the disease-spreading Laclede Lake to the clearing of Mill Creek Valley. He concluded that “progress won” when the lake that Pierre Laclede created was drained for health reasons, and that progress won again with the destruction of Mill Creek Valley.

Again, further research into The Argus and The American will be needed to have a well rounded understanding of how all segments of St. Louis felt about the clearing project.

Similar Projects

Multiple cities across the United States took advantage of Title I of the Housing Act of 1949 to blight and clear large tracts of land in the middle of, or nearby, downtown districts. Most, but not all, examples of clearance that took place near the time frame of the Mill Creek Valley project involve neighborhoods with majority African American populations, which were displaced and resettled in public housing projects.

New York City, for example, lost multiple blocks of 98th and 99th Streets in the 1950s after passage of Title I of the 1949 Housing Act.[17] Residents denied that the area was distressed, but Robert Moses, chairman of the New York City Slum Clearance Committee, labeled it a slum and erected middle-income apartment buildings in their place.

The soon to be displaced youth of 98th and 99th Streets.

Just a few hours drive from St. Louis, 50,000 families were displaced in Chicago due to blighting by the Chicago Land Clearance Commission from 1948-1963.[18] This was due in part to the construction of the Dan Ryan Expressway and the construction of housing projects, which replaced neighborhoods that the Chicago Land Clearance Commission deemed as slums throughout the city.[19]

Between 1958-1961 alone, the Chicago Land Clearance Commission spent 10.5 million dollars to demolish over 1,000 homes and relocate the families, many of whom ended up in public housing projects that were razed just a few decades after their construction.[20]

Bronzeville, a predominantly African American neighborhood in Chicago that was known as the Black Metropolis, was similar to Mill Creek Valley in that it was a hub for artists and musicians; Louis Armstrong and Sam Cooke played clubs in Bronzeville, and famous black actors and other luminary figures lived and worked in this neighborhood.[21] The large chunks of Bronzeville were blighted and turned into public housing projects like the infamous Robert Taylor Homes in the early 1960’s, due to city officials concerns about the neighborhood. The Robert Taylor Homes buildings were demolished 1995-1998, after the structures had long since decayed and the residents were subjected to crime and failing services.[22] Some of Bronzeville remains today, with plaques and historic sites to mark the area, unlike Mill Creek Valley’s erasure from maps and memories.

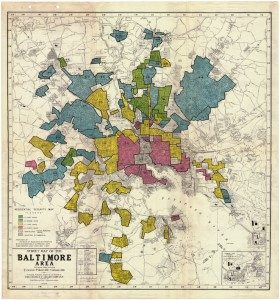

In contrast to the clearance of Mill Creek Valley in St. Louis, 98th and 99th Streets in New York City, and Bronzeville in Chicago, Baltimore took a different approach in some of its neighborhoods. The Baltimore Plan of 1953 identified slums, then sent police, firemen, the housing department, and sanitation department to perform inspections and cite owners for violations.[23] The plan looked at individual buildings instead of razing whole neighborhoods, which appears on the surface to be a more deliberate, effective method of revitalization.

However, the plan did not achieve its desired goals, and residents continued to live in substandard housing after the Baltimore Plan ran out of funding and credibility. Despite exploring other tactics to deal with blight, Baltimore also razed neighborhoods using Title I of the Housing Act – many families were displaced due to blighting and eminent domain acquisitions for highway construction. As Emily Badger writes in a Washington Post article responding to the death of Freddie Grey, “from 1951 to 1971, 80 to 90 percent of the 25,000 families displaced in Baltimore to build new highways, schools and housing projects were black. Their neighborhoods, already disinvested and deemed dispensable, were sliced into pieces, the parks where their children played bulldozed.”

Conclusion

In project after project, whether in St. Louis, New York, Chicago, or Baltimore, a common theme emerged; nearly every area cleared in city after city contained a large percentage of African American residents, leading many to equate “urban renewal” with “negro removal.” Many of these areas were cleared and left vacant for years, if not decades, before the development promised took place, earning areas like Mill Creek Valley the infamous nickname “Hiroshima Flats.” Some federal urban renewal laws required that compensation be awarded to those who were displaced to cover the costs of new housing, while others did not. Even when displacement took place under laws that required compensation in St. Louis, only about half of the African Americans displaced were offered any type of relocation assistance.[24] When relocation assistance was offered, many of these residents felt that the price they paid was much steeper than what they got in return. Their lives had been disrupted, their roots upended, and many found themselves moving over and over again in an attempt to escape the urban renewal bulldozer.

Bibliography

“A Retrospective Look at the Clark-North Avenue SW Corner.” James Kilmer History: North & Clark Retrospective, (N.p., n.d.), accessed May 8, 2017.

Abbot, Mark. “The 1947 Comprehensive City Plan and Harland Bartholomew’s St. Louis,” in St. Louis Plans: The Ideal and the Real St. Louis, edited by Mark Tranel, (Missouri Historical Society Press, 2007).

Baumhauf, Richard. “Progress or Decay? St. Louis Must Choose.” PROGRESS OR DECAY? ST. LOUIS MUST CHOOSE. University of Missouri – St. Louis, n.d., accessed May 8, 2017.

Bloom, Nicholas Dagen. Merchant of Illusion James Rouse, America’s Salesman of the Businessman’s Utopia. (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2004).

Conn, Steven. Americans against the City: Anti-urbanism in the Twentieth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

Ernest Calloway Speech, March 17, 1958. University of Missouri – St. Louis, n.d., accessed May 8, 2017.

Gordon, Colin. Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the Fate of the American City (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008).

“History of Bronzeville,” Bronzeville Area Residents’ and Commerce Council, (N.p, n.d.), accessed May 8, 2017.

McRoberts, Flynn. “Robert Taylor Homes Public-housing Project,” Chicagotribune.com, August 27, 2008, accessed May 8, 2017.

Rothstein, Richard. “The Making of Ferguson: Public Policies at the Root of its Troubles,” (Economic Policy Institute, 2014).

Sandweiss, Eric. St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001).

Schweber, Nate. “A Community Erased by Slum Clearance Is Reunited,” The New York Times, October 9, 2011, accessed May 8, 2017.

Spencer, Thomas. The Other Missouri History Populists, Prostitutes, and Regular Folk (Columbia: University of Missouri, 2004).

St. Louis Development Program, “Technical Report on the History of Renewal” (St. Louis: City Planning Commission, 1971).

Taylor, Dorceta. Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 254.

“Urban Decay in St. Louis” (St. Louis: Institute for Urban and Regional Studies, Washington University, 1972).

“Urban Renewal,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, (N.p., n.d.), accessed May 8, 2017.

[1] Mark Abbot, “The 1947 Comprehensive City Plan and Harland Bartholomew’s St. Louis,” in St. Louis Plans: The Ideal and the Real St. Louis, edited by Mark Tranel, (Missouri Historical Society Press, 2007), 109.

[2] “Urban Decay in St. Louis” (St. Louis: Institute for Urban and Regional Studies, Washington University, 1972), 13-14.

[3] Eric Sandweiss, St. Louis: The Evolution of an American Urban Landscape (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2001), 228.

[4] St. Louis Development Program, “Technical Report on the History of Renewal” (St. Louis: City Planning Commission, 1971), 12.

[5] Colin Gordon, Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the Fate of the American City (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008), 163.

[6] St. Louis Development Program, 12.

[7] Ibid., 14.

[8] Ibid., 16.

[9] St. Louis Post-Dispatch (August 8-10, 1954).

[10] Dorceta Taylor, Toxic Communities: Environmental Racism, Industrial Pollution, and Residential Mobility (New York: New York University Press, 2014), 254.

[11] Richard Rothstein, “The Making of Ferguson: Public Policies at the Root of its Troubles,” (Economic Policy Institute, 2014), 23.

[12] Thomas Spencer, The Other Missouri History Populists, Prostitutes, and Regular Folk (Columbia: University of Missouri, 2004), 104.

[13] St. Louis Development Program, “Technical Report on the History of Renewal” (City Plan Commission, 1971), 19.

[14] Ibid., 6.

[15] Ernest Calloway Speech, March 17, 1958. University of Missouri – St. Louis, n.d., accessed May 8, 2017.

[16] Richard Baumhauf, “Progress or Decay? St. Louis Must Choose.” PROGRESS OR DECAY? ST. LOUIS MUST CHOOSE. University of Missouri – St. Louis, n.d., accessed May 8, 2017.

[17] Nate Schweber, “A Community Erased by Slum Clearance Is Reunited,” The New York Times, October 9, 2011, accessed May 8, 2017.

[18] “Urban Renewal,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, (N.p., n.d.), accessed May 8, 2017.

[19] Steven Conn, Americans against the City: Anti-urbanism in the Twentieth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 187.

[20] “A Retrospective Look at the Clark-North Avenue SW Corner.” James Kilmer History: North & Clark Retrospective, (N.p., n.d.), accessed May 8, 2017.

[21] “History of Bronzeville,” Bronzeville Area Residents’ and Commerce Council, (N.p, n.d.), accessed May 8, 2017.

[22] Flynn McRoberts, “Robert Taylor Homes Public-housing Project,” Chicagotribune.com, August 27, 2008, accessed May 8, 2017.

[23] Nicholas Dagen Bloom. Merchant of Illusion James Rouse, America’s Salesman of the Businessman’s Utopia. (Columbus: Ohio State University Press, 2004), 71.

[24] Rothstein, 23.