By Stephanie VanCardo and Peter Taylor

Black and white people want similar things. “People have a lot more in common than they think. They all want safe neighborhoods. They all want investment. They all want access to services. They want to live next to civic minded neighbors and they want their kids to go to neighborhood-based schools” (https://commonreader.wustl.edu/c/touring-divided-city/). Although this seems simple enough, Americans struggle to define equality. Until 1847, public schools for African-Americans were outlawed in Missouri. Children were educated in churches or on riverboats. Instead of fighting, John Bathan Vashon, promoted the idea of education as a way for African Americans to acquire a better life.

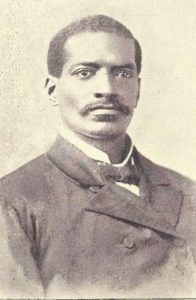

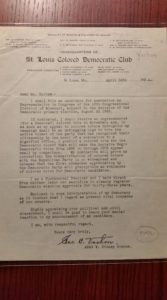

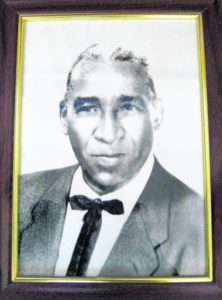

He complained that two decades (1830-1850) of fighting had not improved the free African-Americans’ situation. John believed that education was the primary tool through which African-Americans could improve their condition. He made sure his son, George Boyer Vashon, received a good education. George was the first African-American to graduate from Oberlin College, and the first African American lawyer in New York. In 1853, a “Colored” National Convention was held in Rochester, New York. Convention leaders, including John and George, demanded justice and equality for African Americans. The agenda included three interrelated elements of self-improvement: moral improvement, education and self-help. George was prominently involved in the civic and political affairs of St. Louis. George and his wife, Susan spent their lives teaching African-American students. They were influential role models for their son, John Boyer Vashon who was born in 1859. Spending most of his childhood in Pittsburgh and Washington, DC, he didn’t arrive in Saint Louis until the late 1880’s. Continuing the legacy as a school principal and teacher, he gained the reputation as outstanding educator. He made major contributions to the religious, cultural and civic life of Saint Louis (Mahoney, John. “Long Day’s Journey Into Light”).

In 1865, Missouri passed a revised state constitution which allowed African-American children to be educated. Then in 1896, Plessy v. Ferguson gave lawful power to the separate-but-equal doctrine, which kept black and white children apart across schools, nationally. The problem was that separate did not mean equal. “Schools for African-American children began to operate in Saint Louis. Records indicate that the “white” schools were funded at three times that of the “colored” schools. In addition, “colored” schools were not neighborhood schools in the same sense as the white schools. African-American children often had to go long distances to get to their schools, often passing on the way many “white” neighborhood schools” (Mahoney, John. “Long Day’s Journey Into Light”).

In the first few decades of the twentieth century, St. Louis embarked on an extensive public school building campaign. Architect, Rockwell M. Milligan brought a unified style of design to neighborhoods schools across St. Louis. Sumner, the only African-American high school was located just west of the Ville neighborhood, was suffering from severe overcrowding, and was a good distance from Mill Creek Valley. So, in 1922, The Central School Patron Association began planning for a second-high school that would be constructed by, named after, and designated for African-American students. Five years later, Vashon High School opened on September 6, 1927 at 3026 Laclede Avenue, on budget ($1,180, 790) and on time.

St. Louis’ population had reached 821,960 by 1930. Almost 300 teachers were employed to teach 116,202 public school students. By 1933, 152 schools had been built, which resulted in massive cutbacks: salary cuts, job repositioning, and lay-offs. Building construction and all major repairs and alterations were postponed. Two million dollars in bonds were authorized in 1934 for school building repairs, yet the 1939 Strayer Survey condemned many of the 19th century schools still in use (Toft, Carolyn. Education and Design: The St. Louis Public School Buildings).

In 1954, the landmark Brown v. Board of Education reversed the Plessy v. Ferguson decision, saying that separate education was, by definition, unequal.

In Missouri, black society members managed to build separate but-equal communities, some of which were successful at maintaining a separate-but-equal society with equivalent but segregated public school systems. Many black St. Louisans lived in a separate society, where public schools were less discriminatorily funded in comparison to their Southern counterparts. Prior to Brown, a biracial committee of educators provided Missouri students with the same curriculum, textbooks, and term lengths. School districts spent equal amounts of money on their pupils. Many black teachers and administrators regarded their school as adequate or better. One of the biggest areas of concern was the impact of integration on black schools, principals, and teachers. School districts were drawn according to already standing neighborhoods, so desegregation provided little or no results. Many black educators and parents feared it would demolish successful black institutions, and reduce black employment opportunities. Lack of cultural leadership provided by African American teachers would cause black students to lose interest in becoming teachers, and general concern that white teachers would not be able to teach black students due to intolerance or lack of understanding. Although black St. Louisans were less concerned with social equality and more concerned with job availability, housing, and education, they were concerned that imposed assimilation into white culture would cause the disappearance of African-American culture.

In 1955, an article in the Journal of Negro Education discussing the status of integration in Missouri schools stated, “all Negro children chose to continue at the Negro school” in Poplar Bluff. This fact was reiterated on February 13, 1956, when the Poplar Bluff Daily American featured an article with the headline “Both Races Appear Satisfied with Separate Schools in S.E. Mo.” Al Daniel, the author of the article, expressed that there was no demand for public school integration and since no African American students had applied for admission to any all-white schools, none had been refused. The St. Louis Argus quoted Representative Tyus: “the legislator said the group was made up of those persons who stand to ‘gain by segregation’ and so would stymie progress in the state.” According to the Argus, the group was “working toward an amendment or bill which would safeguard Negro teachers’ jobs in the event segregation is abolished.” An editorial in the Chicago Defender blatantly identified the fear of the loss of black teachers’ jobs as a fallacy, agreeing that because African Americans had limited employment opportunities, the education field was more concentrated with African Americans; therefore, more African Americans are likely to get hired. Another result of this, it noted, was that “many Negro teachers [would] be absorbed into jobs of greater remuneration and scope.”

Following the Brown decision, less than fourteen percent integrated after the Brown decision, most black students remained in their school district, and both all-black schools remained open. Brown did not result in the mass firing of black St. Louis educators, mostly because St. Louis, was home to half of the African Americans in Missouri, and they had strong community support. In this instance, the community represented a safety net for black teaching jobs. However, this was not the case throughout Missouri or the nation. (http://www.lindenwood.edu/files/resources/blackresistancetoschooldesegregationinstlouisdurin.pdf

St. Louis’ great achievement didn’t banish prejudice or poverty, nor did it freeze population numbers, or biased attitudes. St. Louis did not move far between 1955 and 1962. In some ways, the pattern has been retrogressive. From the beginning of desegregation, Negro teachers in predominantly white schools have been few. On balance, de facto segregation in St. Louis public schools has patently worsened during the last 7 years. Just as feared, Brown v. Topeka didn’t fully address the issue of de facto segregation brought on by housing patterns. Blacks were relegated to their own city neighborhoods, where children attended neighborhood schools. When housing is segregated, so are schools. Funding, and educational quality, receded during the 1950s and 1960s. What had once been one of the best public school systems in the United States had plummeted. Black students especially suffered as public schools declined in a core city with a disproportionately high African-American population (https://www.law.umaryland.edu/marshall/usccr/documents/cr12sch63.pdf).

Early in the 60’s the enrollment of Vashon had severely diminished. The Mill Creek Valley area had been targeted to make room for an expanding central business district. The neighborhood was systematically dismantled. Families were directed to relocate away from Vashon. With the population dropping, operating Vashon was no longer cost effective. The St. Louis Board of Education voted to close Vashon High School at 3026 Laclede Ave. Operated by the St. Louis Public School district, the Vashon Building would assume the name Harris Teachers College. Unfortunately, the building was preserved, but the name was not (http://www.slps.org/domain/2956).

At the beginning of the 1963-64 school year, Vashon’s high school history would be continued in its new location at 3405 Bell Avenue. Hadley Technical High School was built in 1931 by architect George W. Sanger. It was named after Herbert Spencer Hadley; a former governor of Missouri, and was sizably comparable to a massive warehouse. In 1950, Hadley students relocated to O’Fallon Technical High School on Northrup Avenue. Black students were being expelled from a school built exclusively for them, and placed in a second-hand structure that had housed whites only. Although the move created some animosity, Vashon blossomed in its new location. Staff, students and faculty continued with the same high educational standards, drive and determination that prevailed on Laclede Avenue. Academics flourished and the athletic prowess of its students gained national recognition from basketball teams coached by George Cross, Ron Coleman and Floyd Irons. The Marching Wolverines, directed by O’Hara Spearman, was a much sought after addition to every parade or celebration all over St. Louis. The Thespian Society, under the guidance of Aaron E. Murphy, produced and directed a biannual variety show titled, “Vashon Requests the Pleasure.” (http://www.slps.org/domain/2956)

Public education in St. Louis came under court supervision in 1980, with the goal of desegregating public schools. At that time, three out of four students enrolled in St. Louis Public Schools were black, while more than two out of five white students attended schools outside the system. Each day from 1983 until 1999, thousands of city children were bused to county schools, leaving the city schools nearly abandoned. In the mid-80’s a school bond issue provided millions of dollars for school renovations as part of the 1972 segregation lawsuit settlement (http://www.slps.org/domain/2956).

Conditions in the Vashon building were described as, “a disgrace, a most unfitting educational climate for the young men and women who are entitled by law to much better facilities.” Alumni asked the Board of Education when Vashon would be renovated. The answer was not what they expected to hear. Funds allocated for the renovation of Vashon had been spent on other schools because the Board was considering closing Vashon High School. Several community leaders, including, two members of the original alumni group, (Vitilas “Veto” Reid, and Robert Spain) became the, Save Vashon Committee. Reid and Spain engaged in a ten-year battle with the Board of Education, the State of Missouri, and numerous federal judges to build a new facility. Court ordered busing continued during this ten years. The state of Missouri wished to be relieved of this financial obligation, they felt that St. Louis Public Schools had done enough to help desegregate schools. William H. Danforth was court appointed to negotiate a settlement. Major capital improvements were included as part of the agreement. The building of several new schools would accommodate more than 14,000 students who would return to the district once busing came to an end. Once again, funding for Vashon High School became a major issue (http://www.slps.org/domain/2956).

In 1998, the state passed Senate Bill 781. Missouri financially agreed to off-set funds, if the court order ceased, however, there was a provisional tax increase that required St. Louis to raise additional funds before State money would be issued. That following year, St. Louisans were asked to support a tax increase to help fund existing school renovations, and the construction of several new schools in north and south St. Louis. The collaborative effort of community organizations in north and south St. Louis helped pave the way for a new Vashon High School (http://www.slps.org/domain/2956).

Fifteen years of persistence finally pays off. In September of 2002, Vashon High School opened in its third location at 3035 Cass Avenue. The 40 million- dollar, state-of-the- art complex, houses 1,300 students, has 13 science and computer labs, 4 early childhood rooms, an attractively spacious library and media resource center surrounding the sky-lighted rotunda. For basketball, there are competition and practice courts, and a 25-meter swimming pool for aquatics programs (http://www.slps.org/domain/2956). In 2003, the Julius C. Dix Auditorium, a 500-theater seated, semi-circle was added at an additional cost of $2.5 million dollars. The old building was demolished in January of 2003.

The students established Vashon as a premier educational institution known for its academic curriculum and superior athletic programs. Students sharpened their talents to pursue careers as future educators, community leaders, politicians, clergymen, homemakers, professional and entrepreneurs.

In 1961 Pearlie Evans was a Vashon student and Civil Rights leader who helped integrate public accommodations in St. Louis. She was an activist with the Congress for Racial Equality and the NAACP. She marched with future Congressman William Clay, Norman Seay, Percy Green II. Later she served as the top aide to the first African-American congressman from Missouri (Ross, Gloria. St. Louis American).

Patrobas Cassius Robinson, a St. Louis, Mo., native graduated in 1927 with a bachelor’s degree in chemistry. Robinson taught science classes at Vashon High School for 35 years. In addition to teaching, he operated the P.C. Robinson Realty Co. in St. Louis from 1945 until 1980, when he retired. He was also one of the founders of the National Society of Real Estate Appraisers, an African American organization (http://spectator.uiowa.edu/2010/june/oldgold.html)

Seay is a founding member of the legendary Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). He spent three months in jail for participating in protests that sought jobs for African Americans in St. Louis banks and financial institutions. The protests included the monumental Jefferson Bank & Trust Co. pickets in 1963. (Revis, Rebecca. St. Louis American).

Vashon’s graduates are among the famous, the known, and the unknown. Some lost their lives. Some went on to be great athletes, and entertainers. Some walk among us. All were part of the fight for African-American justice. In the face of destruction, it is human resilience and persistence that remain in tact. We all want freedom. Education is a freedom recognized through great movements instead of great wars.

Works Cited

“Education and Design: The St. Louis Public School Buildings.” Landmarks Association of St. Louis. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 May 2017.

Mahmoud, Jasmine. “Touring the Divided City.” Common Reader. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 May 2017.

Mahoney, John Patrick. Long Day’s Journey Into Light”. N.p.: n.p., n.d. 1-6. Print.

McCulley, Jessica. “Black Resistance to School Desegregation in St. Louis During the Brown Era.” The Confluence. N.p., n.d. Web. 05 May 2017.

Old Gold – Spectator@IOWA – Monthly News for UI Alumni and Friends – The University of Iowa. N.p., 01 June 2010. Web. 10 May 2017.

Rivas, Rebecca. “Norman Seay Is White House-bound.” St. Louis American. N.p., 12 Dec. 2013. Web. 10 May 2017.

Ross, Gloria S. “Pearlie I. Evans, Activist and Powerful Aide to Former U.S. Rep. William L. Clay, Passes at 84.” St. Louis American. N.p., 22 Nov. 2016. Web. 10 May 2017.

Staff Reports, comp. “Civil Rights USA: Public School Cities in the North and West.” US Commission on Civil Rights. (n.d.): n. pag. Thurgood Marshall Law Library; The University of Maryland School of Law, 1962. Web. 5 May 2017.

“Vashon High School.” History of Vashon / Overview. N.p., n.d. Web. 10 May 2017.